Climate Change on the Third Pole: Causes, Processes and Consequences. (Scottish Parliament, 2021)

- Martin Mills

- Jul 16, 2023

- 4 min read

In January 2021, the Scottish Parliament's Cross-Party Group on Tibet, supported by the Scottish Centre for Himalayan Research at the University of Aberdeen, published Climate Change on the Third Pole: Causes, Processes and Consequences. Originally distributed to the Scottish, UK and other parliaments, you can now read it here.

Prompted by the growing conundrum of widespread flash desertification and across the Tibetan Plateau, the inquiry reviewed over seven hundred scientific publications from universities, research institutes and NGOs all over the world. The report reveals the growing consensus that the Third Pole Region is undergoing a major climate and environmental shift.

Summary

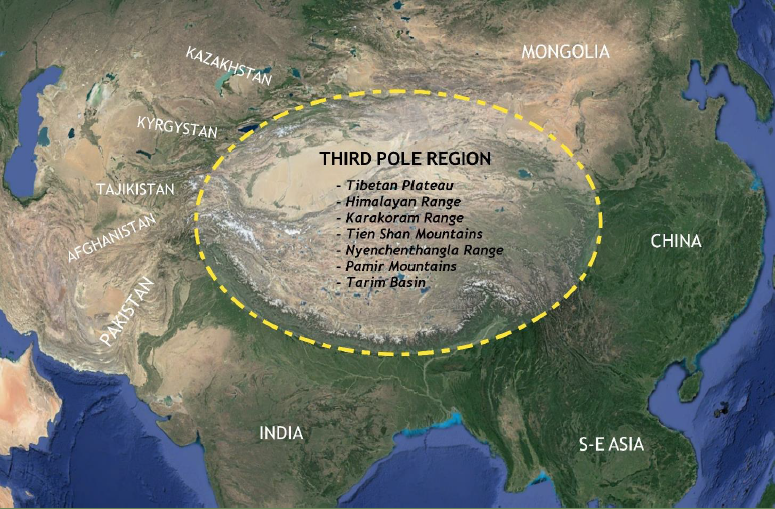

The Tibetan Plateau and surrounding mountain ranges from space. Courtesy: NASA.

1. The Third Pole Region (TPR) is a high-altitude massif at the heart of Asia comprising the Tibetan Plateau and its surrounding mountain ranges: the Himalaya, Karakorum, Pamir and Tien Shan Ranges (see Fig.1) amongst others. Nearly the size of Europe and at an average altitude of 4,000 meters above sea level, the Plateau’s glaciers, snow and permanently frozen ground (permafrost) – its cryosphere – contains within it the largest mass of frozen freshwater outside of the polar regions, leading to it often being called “The Third Pole”.

Major Asian rivers that have their sources in the Third Pole. Courtesy: Michael Buckley.

2. The TPR cryosphere depends on snowfall and freezing winters, storing frozen freshwater at high altitude. Its gradual melting throughout the rest of the year, augments river flow in spring and summer, regulating the overall water supply to the surrounding region. The cryosphere’s ‘buffering’ of Asia’s water cycles thus provides the region’s rivers with consistent supplies of freshwater throughout the year. The headwaters of ten major rivers are found in the TPR uplands: the Yellow & Yangtse Rivers feeding to the east; the Mekong, Salween, Irrawaddy & Brahmaputra to the south; the Ganges, Sutlej & Indus Rivers to the west; and the Tarim River to the North. In total, 1.9 billion people live within the watersheds of these rivers and depend upon them directly for freshwater supplies, and some 4.1 billion people are fed by agriculture and industry dependent upon these supplies – more than half the world’s present population.

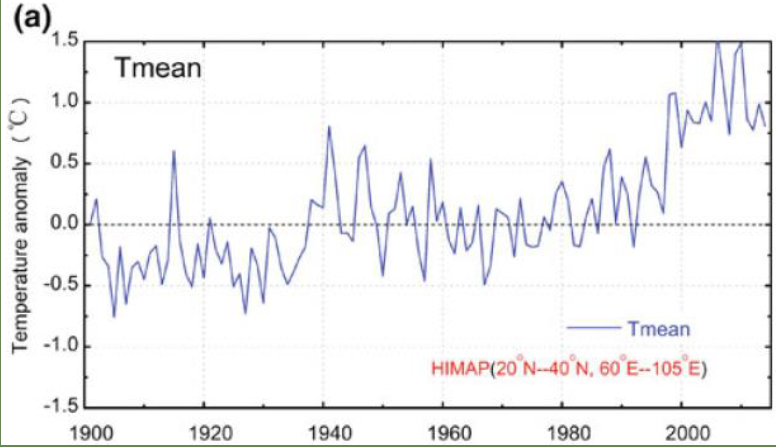

Mean temperature changes on the Tibetan Plateau across the last century. Source: Khrishnan et al. 2019: 66

3. There is clear evidence that temperatures across the TPR are increasing at a rate between two and four times the global average, a process that has been underway for more than half a century. This primarily involves an increase in minimum winter temperatures, compromising the region’s capacity to maintain Climate Change on The Third Pole Scottish Centre for Himalayan Research a viable cryosphere: glaciers are reducing in size, permafrost is melting, snowfall is turning to rain: the overall pattern is for the Tibetan Plateau in particular to become progressively warmer and wetter. The causes of these changes include global atmospheric warming, regional pollution, local land-use patterns and a growing range of complex feedback processes, but undoubtedly the most substantial driver is global atmospheric warming. Indeed, the conditions for the loss of the majority of glaciers and permafrost across the TPR are already established at present temperatures.

4. Without significant changes to the present direction of global climate change, the impact of these changes over the next fifty years include: increased flooding south of the Himalayas; escalating disruption of human infrastructure in permafrost areas; the desertification of high-altitude river headlands and grasslands in eastern Tibet; and the loss of freshwater supplies to mountain communities and urban centres downstream of the TPR, particularly those in India, Pakistan and Xinjiang that depend on glacial meltwaters. Along the same timetable, this would involve a destabilization of year-round freshwater resources to inland regions around the TPR. Local access to significant freshwater supplies is a hard adaptation limit for human communities, agriculture and industry, and its destabilization would have a direct impact on the population maintenance, agriculture and industry of 220 million people and the continent’s resilience to desertification.

5. Several major policy lessons can be learnt from Asian states’ struggles to both mitigate and understand these changing environmental conditions:

a. Many of the systemic changes that are only now impacting human populations have already been underway for decades and are already well-established at present global temperatures.

b. Many climate change effects (such as glacier and permafrost melt) depend on non-negotiable physical and biological thresholds (such as the 0C threshold between ice and water), crossing which may precipitate abrupt ecological shifts.

c. Climate change processes often combine in ways that produce complex and counterintuitive effects, at odds with the abstracted ecological models and precedents for individual processes. Transferring mitigation policies from one ecological zone to another ignores these complex local interactions and may well produce damaging and counterproductive results.

d. Some of these effects (such as upland desertification) may prove transitional, appearing and disappearing as climate change progresses through distinct stages. Long-term mitigation strategies need to take this into account.

e. Realistic projections of the effect of climate change require regional assays of specific ecologies, based on a stronger weight of on-the-ground empirical data (as opposed to mathematical modelling) than is presently available. International data sharing is an essential component of this.

Published by the Scottish Parliament's Cross-Party Group on Tibet and the University of Aberdeen's Scottish Centre for Himalayan Research

Comments